Carnivore Diet: What Does Science Say About Eating Mostly Meat?

Why do some people feel better on a carnivore diet?

Some people report feeling better after switching to the carnivore diet (a diet of only animal-based products such as meat, fish, and eggs). Often, this improvement happens because they previously consumed a lot of processed foods and are now eating more unprocessed products. Others with digestive issues, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease, sometimes experience short-term relief when following a carnivore diet.

On social media, advocates of the carnivore diet often share personal stories about reduced symptoms after switching from a plant-based or mixed diet to one rich in meat, fish, and eggs. The improvement can often be explained by moving away from processed, sugar-heavy foods to an unprocessed diet (1–6).

In particular, people with digestive complaints—such as IBS, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or celiac disease—may experience symptom relief in the short term. A low-fiber diet (usually high in animal products) can reduce gas and bloating, since it contains fewer fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) and fibers (7).

The downside of the carnivore diet

While a low-fiber diet may temporarily reduce digestive complaints, it negatively affects the gut microbiome over time. The diversity of gut bacteria decreases, beneficial bacteria decline, and harmful bacteria increase (8). In the long run, this can worsen gut health and increase disease risk.

Studies show that the more plant-based someone eats, the lower their risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). People with IBD who follow a more plant-based diet even have a reduced risk of surgery compared to those consuming more animal-based foods (9).

Below we summarize scientific findings on the carnivore diet in relation to four major health outcomes: inflammation, weight, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. The science is clear: a carnivore diet is not healthy.

At Plants for Health, we don’t cherry-pick studies. We rely on high-quality research such as large systematic reviews and meta-analyses. As doctors, dietitians, and health scientists, we are trained to critically evaluate studies and interpret them in context—something influencers often fail to do when citing a single PubMed article.

1. Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is linked to many diseases including digestive disorders, rheumatic conditions, cardiovascular disease, neurological disease, accelerated aging, and cancer. Reducing inflammation is a key goal of both medical treatments and lifestyle interventions.

There is no evidence that the carnivore diet reduces inflammation. On the contrary, large reviews show that Mediterranean, vegetarian, and plant-based diets most consistently lower inflammatory markers in the blood (10–15). Diets rich in red and processed meat are linked to unchanged or even higher inflammation compared to plant-based diets.

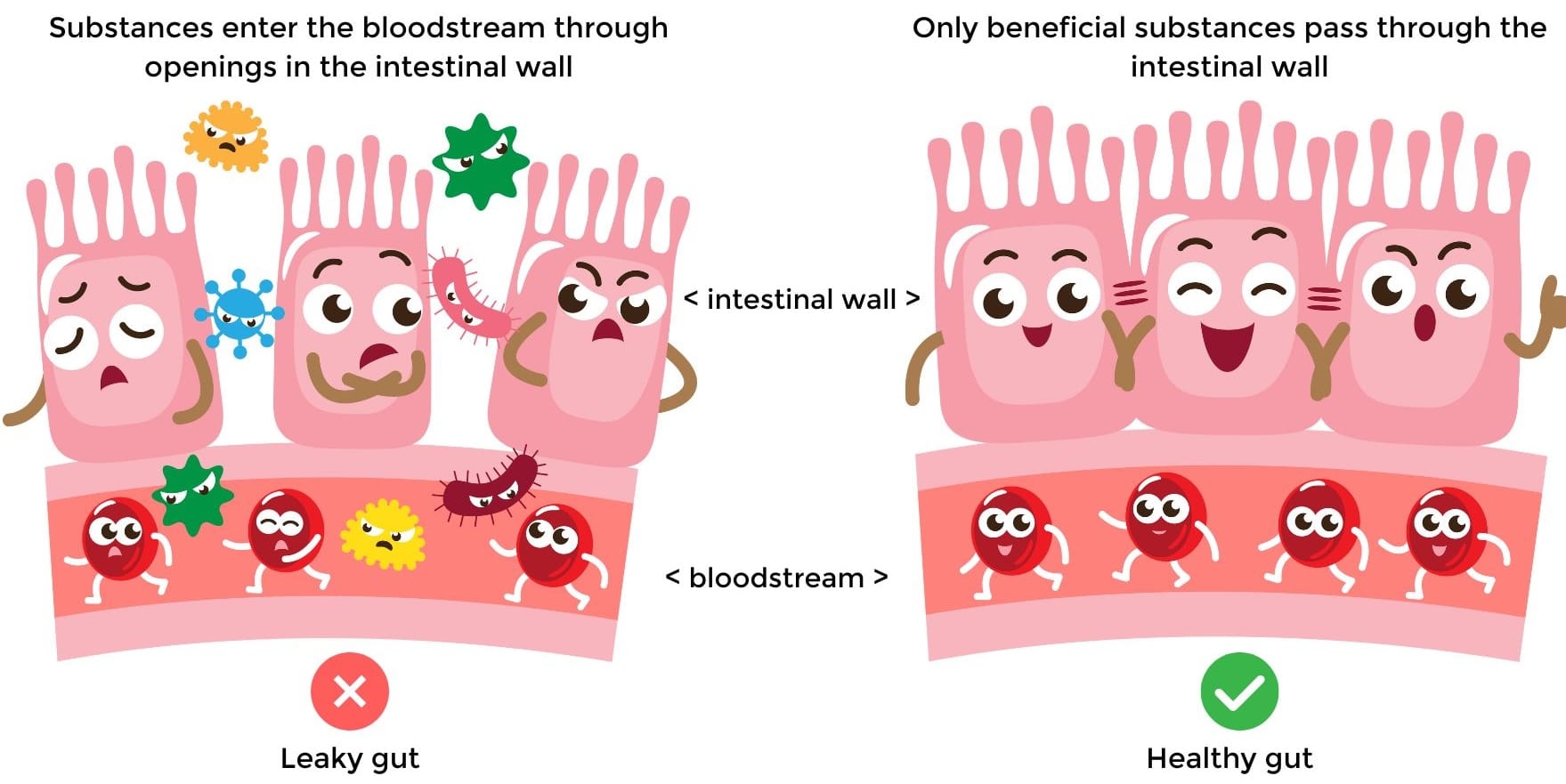

Plant-based foods are rich in fiber and polyphenols. These promote beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids, which are anti-inflammatory and support a healthy gut barrier. A compromised gut barrier (“leaky gut”), which can result from diets high in saturated fat and sugar but low in fiber and polyphenols, allows harmful molecules into the bloodstream and triggers chronic low-grade inflammation (16).

2. Weight

There are no studies showing that a strictly animal-based diet is effective for weight loss. A large review of over 5,000 people showed that calorie restriction combined with physical activity is the most effective method for fat loss and preserving muscle mass (17). Higher protein intake can also help preserve lean body mass (18).

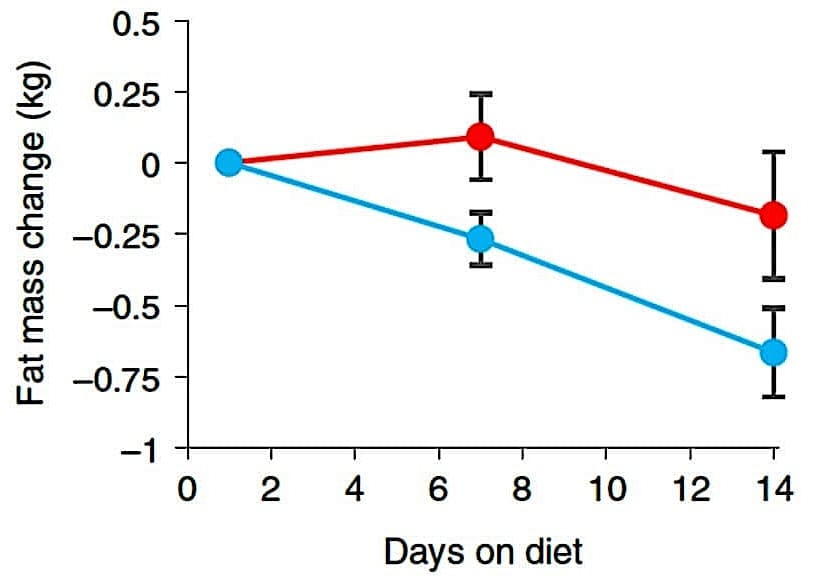

A well-known study by nutrition researcher Kevin Hall, published in Nature Medicine, compared a low-fat, plant-based diet with a high-fat, low-carb animal-based diet (19).

Key findings:

Participants on the plant-based diet spontaneously ate 500 fewer calories per day without feeling hungry.

Participants on the plant-based diet spontaneously ate 500 fewer calories per day without feeling hungry.- Both groups lost weight, but those on the animal-based diet mainly lost water and muscle, while those on the plant-based diet lost more body fat (19).

In short: a negative energy balance is crucial for weight loss. A plant-based diet makes this easier due to lower calorie density, provided you also exercise and consume enough protein to preserve muscle mass.

3. Cardiovascular disease

There is no evidence that the carnivore diet lowers cardiovascular risk. In fact, large studies show that eating more red and processed meat is associated with higher rates of heart disease (20–25).

Conversely, replacing animal proteins with plant proteins is linked to lower cardiovascular risk (21,23,25). This is why international cardiology associations emphasize that diets high in meat and animal fats increase the risk of heart disease, while Mediterranean and plant-based diets lower it (24).

4. Cancer

The carnivore diet is, by definition, high in red meat and often processed meat. Processed meats such as bacon, ham, and beef jerky are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as carcinogenic—on the same list as tobacco (26).

WHO advises limiting meat intake, especially processed meat, and reducing red meat consumption to lower cancer risk (26).

Plant-based diets are consistently associated with lower cancer risk and better outcomes in cancer survivors. A large study found vegetarians had a 12% lower risk of developing cancer and vegans a 24% lower risk compared to omnivores (27).

Population studies show that diets low in plant foods but high in animal proteins and fats are linked to higher cancer risk and mortality (28–30). For this reason, the World Cancer Research Fund recommends focusing on whole, unprocessed plant foods and minimizing red and processed meat intake.

Should I eat fully plant-based?

A fully plant-based diet is healthy—when properly planned. But even a mostly plant-based diet with some animal products can be beneficial. The most important advice:

- Avoid red and processed meat.

- Focus on whole, plant-based foods: vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds.

- If you have digestive issues, increase fiber gradually or seek guidance from a dietitian.

Conclusion: the science on the carnivore diet is clear

The evidence is overwhelming: the carnivore diet is not healthy. While some people experience short-term relief, long-term studies show higher risks of inflammation, weight gain, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Take the next step with Plants for Health

Want to reduce your risk of inflammation, obesity, heart disease, and cancer? Or improve outcomes if you’re already managing a chronic condition? At Plants for Health we help people with chronic conditions gain more control over their health through a scientifically proven lifestyle program.

Learn more about the Plants for Health book, filled with recipes and evidence-based guidance, and our Plants for Health program, where our experts guide you step by step toward a lifestyle that truly works—and lasts.

You might also find this interesting:

Sources

- Forde CG, Decker EA. The importance of food processing and eating behavior in promoting healthy and sustainable diets. Annu Rev Nutr. 2022;42:377399. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-062220-030123.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(2):341354. doi:10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341.

- Jew S, AbuMweis SS, Jones PJ. Evolution of the human diet: linking our ancestral diet to modern functional foods as a means of chronic disease prevention. J Med Food. 2009;12(5):925934. doi:10.1089/jmf.2008.0268.

- Masharani U, Sherchan P, Schloetter M, Stratford S, Xiao A, Sebastian A, et al. Metabolic and physiologic effects from consuming a huntergatherer (Paleolithic)type diet in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(8):944948. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2015.39.

- Frassetto LA, Schloetter M, MietusSnyder M, Morris RC Jr, Sebastian A. Metabolic and physiologic improvements from consuming a Paleolithic, huntergatherer type diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(8):947955. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.4.

- Yannakoulia M, Scarmeas N. Diets. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(22):20982106. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2211889.

- Chey WD, Hashash JG, Manning L, Chang L. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022 May;162(6):1737-1745.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.248.

- Bolte LA, Vich Vila A, Imhann F, Collij V, Gacesa R, Peters V, et al. Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features of the gut microbiome. 2021;70(7):1287-1298. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322670.

- Chen J, Sun Y, Dan L, et al. Composition of plant-based diets and the incidence and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease: a multinational retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2025;52:101264. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101264.

- Reyneke GL, Lambert K, Beck EJ. Dietary patterns associated with anti‑inflammatory effects: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and metaanalyses. Nutr Rev. 2025;nuaf104. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaf104.

- Koelman L, Egea Rodrigues C, Aleksandrova K. Effects of dietary patterns on biomarkers of inflammation and immune responses: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2022;13(1):101115. doi:10.1093/advances/nmab086.

- Mukherjee MS, Han CY, Sukumaran S, Delaney CL, Miller MD. Effect of anti‑inflammatory diets on inflammation markers in adult human populations: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2022;81(1):55‑74. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuac045.

- Norde MM, Collese TS, Giovannucci E, Rogero MM. A posteriori dietary patterns and their association with systemic low‑grade inflammation in adults: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(3):331‑350. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaa010.

- Barbaresko J, Koch M, Schulze MB, Nöthlings U. Dietary pattern analysis and biomarkers of low‑grade inflammation: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(8):511‑527. doi:10.1111/nure.12035.

- Papier K, Hartman L, Tong TYN, Key TJ, Knuppel A. Higher meat intake is associated with higher inflammatory markers, mostly due to adiposity: results from UK Biobank. J Nutr. 2022;152(1):183189. doi:10.1093/jn/nxab314.

- Randeni, N., Bordiga, M., & Xu, B. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of the Triangular Relationship among Diet–Gut Microbiota–Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(17), 9366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25179366

- Xie, Y., Gu, Y., Li, Z., He, B., & Zhang, L. (2024). Effects of Different Exercises Combined with Different Dietary Interventions on Body Composition: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 16(17), 3007. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16173007

- Leidy HJ, Clifton PM, Astrup A, Wycherley TP, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Woods SC, Mattes RD. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Jun;101(6):1320S-1329S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084038. Epub 2015 Apr 29. PMID: 25926512.

- Hall KD, Guo J, Courville AB, Bremmer J, et al. Effect of a plant‑based, lowfat‑ diet versus an animal‑based, ketogenic diet on ad libitum energy intake. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):344‑353. doi:10.1038/s41591‑020‑01209‑1.

- Petermann‑Rocha F, Parra‑Soto S, Gray S, Pell JP, CelisMorales‑ C, Ho FK, et al. Vegetarians, fish, poultry, and meat‑eaters and cardiovascular disease: UK Biobank. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(12):1136‑1143. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa939.

- Wang DD, Li Y, Nguyen XM, et al. Red meat intake and risk of cardiovascular diseases: the Million Veteran Program. J Nutr. 2024;154(3):886895. doi:10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.12.051.

- Shi W, Huang X, Schooling CM, Zhao JV. Red meat consumption, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(28):26262635. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad336.

- Glenn AJ, Wang F, Tessier AJ, De Souza RJ, Khan TA, Viguiliouk E, et al. Dietary plant‑to‑animal protein ratio and cardiovascular disease risk in three cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;120(6):1373‑1386. doi:10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.09.006.

- Marques‑Vidal P, Tsampasian V, Cassidy A, et al. Diet and nutrition in cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement of EAPC/ACNAP of the ESC. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025;zwaf310. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwaf310.

- Zhao B, Gan L, Graubard BI, Martin CL, Lin JS, Dodd KW, et al. Plant and animal fat intake and overall/CVD mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(10):12341245. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.3799.

- World Health Organization. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/cancer-carcinogenicity-of-the-consumption-of-red-meat-and-processed-meat

- Fraser GE, Butler FM, Shavlik DJ, et al. Longitudinal associations between vegetarian dietary habits and site-specific cancers in the Adventist Health Study-2 North American cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2025;122(2):535-543. doi: 10.1016/j.ajcnut.2025.06.006.

- Wiseman MJ. Nutrition and cancer: prevention and survival. Br J Nutr. 2019;122(5):481487. doi:10.1017/S0007114518002222.

- Steck SE, Murphy EA. Dietary patterns and cancer risk. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(2):125138. doi:10.1038/s4156801902274.

- Shah UA, Iyengar NM. Plant‑based and ketogenic diets as diverging paths to address cancer: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(8):1201‑1208. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.1769